Memory Games, Part I: "The Data Is Available Upon Request"

An Introduction to Cassava Sciences and Their Forgotten Data

The first of a series of posts that will cover the (ongoing) saga of Cassava Sciences and their Alzheimer’s drug candidate, simufilam.

As I put pen to paper—or, er, fingertips to keys—the fires surrounding Cassava Sciences and their lone drug candidate, simufilam, are still only on the outskirts of town. That could change at any moment, as recent reporting has uncovered a Department of Justice criminal probe into the company, as well as an apparently concluded SEC investigation which produced the equivalent of 48 boxes(!) of records. At the center of the vortex, around which all revolves, is an internal investigation by CUNY School of Medicine, already well beyond its stated timelines and about which almost nothing has been disclosed publicly aside from repeated statements by representatives that they “take accusations of research misconduct very seriously.”

Meanwhile, the company has turned to CEO Remi Barbier to vociferously defend them against allegations of research fraud, which surfaced in August 2021 when a whistleblower report in the form of a citizen petition to the FDA was filed by a pair of short-selling biochemists who are otherwise unaffiliated with the company. The report targeted the research of Cassava's longtime contractor, Dr. Hoau-Yan Wang, whose university laboratory serves as the company’s de facto biochemistry lab. From the outset Barbier, whose wife Dr. Lindsay Burns is the lead scientific officer at Cassava and frequent collaborator of Dr. Wang, scoped a path of defiant bluster. In a statement addressing the allegations, he noted that Cassava “does not respond to internet trolls,” declaring instead that “[Cassava's] currency is data. That's how we plan to win.”

Well, I am one of those “internet trolls” I suppose, and I've asked for the data so that perhaps Cassava might, against all odds, “win.” This story, into however many parts it eventually unfurls, is the story of that data—or lack thereof, as it may be. Now over a year later, the only data conjured thus far in service of Cassava's debts has either been deemed counterfeit or merely alluded to like a myth. In the very same public statement quoted above, Barbier made sure to emphasize the “$2 billion dollars of valuation, wiped out in one week by on-line allegations.” Maybe it was simply unfortunate context—a Freudian slip of sorts. Or perhaps, after breaking open the proverbial piggy bank, Cassava Sciences decided that data isn’t their preferred currency after all.

Searching the Research

I mentioned the long odds that Cassava faces as it continues its pair of phase 3 trials for simufilam, and part of the reason that those odds look as long as they do is because of concerted investigatory reports by a veritable who’s who of journalism, each arriving at essentially the same unfavorable conclusion. STAT News was perhaps the first major publication on the case, and found scientists expressing doubts about trial results prior even to the publication of the whistleblower report. An article in the Wall Street Journal followed in November 2021. Beside an interview with Dr. Elisabeth Bik—arguably the preeminent public figure in the field of fraud detection in published scientific literature—the WSJ article had the following to say:

Several other scientists interviewed by The Wall Street Journal said some images in the articles depicting experimental results appear to have been copied and pasted from other sources.

A longer investigative piece in The New Yorker by Patrick Radden Keef followed the WSJ article, focusing primarily on the efforts of Jordan Thomas, a lawyer and former SEC Enforcement Officer crucial to the development of the SEC Whistleblower Program, who represented the biochemists that filed the whistleblowing petition to the FDA. The article stated about Thomas’s efforts to vet the concerns raised by his clients:

At Thomas’s urging, the doctors sent Cassava’s papers to ten prominent experts, including the neuroscientists Thomas Südhof, of Stanford, who received the Nobel Prize in 2013; Roger Nicoll, of the University of California, San Francisco; and Don Cleveland, of the University of California, San Diego.

…

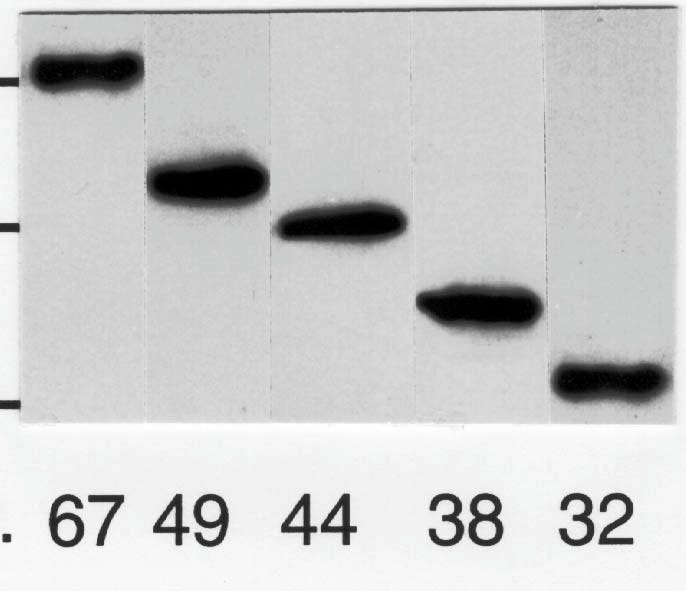

When the scientists consulted Cassava’s research papers, “the main reaction was ‘Oh, my God, how could they get away with this?’ ” Pitt said, adding, “These Western-blot images are hard to fake. It appeared that someone had tried to crop them and cut out little pieces of one and put them in another.”

That was in January 2022. The New York Times chimed in a few months later with an article by Apoorva Mandavilli (who actually contacted me prior to publication regarding an exchange that I’d had with one of Cassava’s scientific advisors, though it doesn’t appear that any of the information that I provided was included in the article). She added to the growing chorus:

The New York Times contacted nine prominent experts for comment about the scientific underpinnings of Cassava’s trials. All said they did not trust the company’s methods, results or even the premise underlying the drug’s supposed effectiveness.

The crescendo came in July, when an explosive piece by Charles Piller in Science shook the entire field of Alzheimer’s research by pulling the curtain down on potential fraud in the work of Sylvain Lesné, whose 2006 Nature article was extremely influential in setting a course for the field (side note: there is some disagreement about how influential Lesné’s work truly was, see the following photo for a bit of context).

And how was the apparent fraudulent research by Lesné discovered? By a neuroscientist and image sleuth, Matthew Schrag, who was hired by Jordan Thomas to help investigate Cassava Sciences only to discover issues more rampant than expected. In a sidebar to the main article, Piller describes his interaction with the stakeholders at Cassava:

Schrag’s sleuthing implicates work by Cassava Senior Vice President Lindsay Burns, Hoau‑Yan Wang of the City University of New York (CUNY), and Harvard University neurologist Steven Arnold. Wang and Arnold have advised Cassava, and Wang collaborated with the company for 15 years.

None agreed to answer questions from Science. Cassava CEO Remi Barbier also declined to answer questions or to name the company’s current scientific advisers.

The scientific community does not appear to have afforded Lesné much leeway in the wake of Schrag’s findings, as the alzforum.org article has become what could be described as a sort of professional obituary, where prominent Alzheimer’s researchers have left numerous comments expressing shock and disappointment. Fundamentally, Schrag’s findings in Wang’s work are no different from his findings in Lesné’s.

Data is the Antidote

The point of assembling such a preponderance of evidence is not to simply assert guilt and hit the gavel, as compelling as it may be. When Barbier spoke of using data as currency, it wasn’t just a metaphorical turn of phrase—everything suspicious about the more than 30 publications with flagged concerns by Wang could dissolve under the weight of raw, original data. After all, these images are representations of physical objects, things that would in theory be stored away, along with a handful of high resolution raw images capturing them during the data recording, analysis, and publication process. Really, there could be any number of ways to produce something from a career’s worth of scientific experiments. This is where it appears that Cassava Sciences, its leadership, and its discordant sideshow of fervent investors have fully lost the plot.

Activist investors, sensing Cassava’s potential for, uh, market “explosivity” let’s say, along with a healthy dose of credulity, joined the company in almost immediately pushing back on these concerns by conjuring ways to dismiss them. A biochemist named Charles Spruck, the anointed hero of the pro-Cassava investor group, supplied a buffet of theoretical explanations for the irregularities to an investor blog, and was referred to in the New York Times article:

Charles Spruck, a cancer researcher at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in San Diego, who has more than 25 years of experience with the Western blot method, said he believed the anomalies in those images could be the result of simple mistakes or vagaries of the technique.

One of the largest individual shareholders in Cassava did his part by devising a series of AI algorithms which failed to recognize any irregularities in the data (hopefully it’s obvious why this doesn’t make sense, but if not the HHS ORI guidelines on forensic analysis may provide clarity). Others shed the veil of diligence and simply declared that the research is of no importance in the first place—Cassava is telling us the drug works, so who cares about some fabricated blotches and a few missing drums of radioactive waste!

The reality is that without some actual raw data, none of these Maginot Lines can hold. The concerns have been validated beyond any reasonable reproach, and the sole way to address them is by producing the data. Cassava had, in essence, two choices once these allegations surfaced: either take the path of thorough diligence, repeat necessary experiments and commit to an open external inquiry; or, batten down the hatches and dismiss everything that comes their way. They’ve chosen the latter. It’s a gambit, no doubt, but it only works if they believe that Wang can come up with some real data. As I plan to cover in more detail in subsequent parts, this has yet to happen after a full year of repeated inquiries. Granted, a handful of unscrupulous journals have helped muddy the waters sufficiently to obfuscate this fact (again, I plan to cover this in more detail later), but as of writing I am not aware of a single piece of credible raw data that has surfaced from Wang’s lab. Perhaps there is a vein yet to be tapped somewhere in the dark corner of the lab where this data resides, but until it’s found the debt collectors will continue to come knocking.