Losing Interest: When Scientific Journals Fail to Take Whistleblowers Seriously

The Journal of Clinical Investigation (JCI) recently featured an editorial by its Editor in Chief which addresses what she feels are ethical breaches by whistleblowers who have been in contact with the journal regarding a a 2012 publication that has come under scrutiny for containing signatures of potential image manipulation. Having received communications from scientists who did not proactively inform JCI of securities positions potentially influenced by their findings, the Editor in Chief now believes that whistleblowers should be expected—perhaps required—to provide a conflict of interest statement when informing the journal of potential misconduct in a published paper. At a glance, this sentiment feels reasonable. With more than a moment’s consideration, however, it unfurls into a complex tapestry that prioritizes financial interest over science integrity and erodes the credibility of the journal as a venue which arbitrates scientific debate using independently verifiable evidence, beholden to no currency other than earnestly collected, reproducible data.

The new policy that the journal has adopted would be problematic enough in a vacuum, but it arrives with context. Only a few days after the publication of the editorial, a defamation lawsuit was filed by Cassava Sciences, a company which should be all too familiar to readers of this newsletter, naming as defendants six scientists who had privately raised concerns to JCI. Both the lawsuit and the JCI editorial reference what the two jointly intimate was a “short and distort” effort undertaken by these scientists. Allegations by Cassava that they have been defamed are run-of-the-mill—we’ve been audience to them for well over a year now—but to see them echoed in a scientific journal is a troubling development. Even more troubling, this editorial is the first official communication from the journal regarding these specific image manipulation concerns. It carries no conflict of interest statement and no disclosures about the nature of correspondence between JCI and officers of Cassava Sciences; it presents no evidence of any material “distortions” or malicious intent; in short, it rings hollow.

Conflicts of Interest: Trust Versus Verify

After beginning the editorial with a brief mention that Science and the New York Times have recently published articles featuring critiques of the 2012 JCI paper, and that these articles also cover Cassava’s lone experimental drug candidate, simufilam, the Editor in Chief continues:

The articles in Science and the New York Times focused primarily on the very serious topic of potential scientific misconduct. However, these articles only lightly touched upon the concept of short selling stock, and I believe this matter deserves more attention for its inherent conflicts of interest.

Scientists, particularly those in academia, are accustomed to disclosing conflicts of interest when they publish or review manuscripts. There are very good reasons for this—research impactful enough to be published generally cannot be verified in a reasonable amount of time, so disclosing conflicts of interest engenders trust that the science was performed as presented. Further, reviewers and editors are in a position of power, and their decisions about whether or not to accept a paper for publication may rely on personal viewpoints about the impact of the research or specific expertise that is, again, not trivial to verify. Whistleblowers can potentially fall into either category, but generally speaking—and certainly in this specific case—these considerations simply do not apply. Alexander Magazinov echoes this sentiment in his response to the editorial on PubPeer:

If a whistleblower comes forward and raises good-faith, easily verifiable concerns, then financial incentives are immaterial. In fact, the federal government actually provides financial incentives to do exactly this! Not only that, but the federal government ensures a fairly robust set of protections for these whistleblowers which generally include anonymity and protection from reprisal. Given that the whistleblower allegations alluded to by the editorial imply securities fraud (not specifically arising from the JCI paper, but as part and parcel to the larger story), one might reasonably expect the editor to extend the same kind of protections that one would receive under the Dodd-Frank Act.

Now, if the JCI editors feel that any parties acted in bad faith by knowingly providing them false information, that would be another matter. That is indeed illegal, and reporting that type of activity to the authorities should be routine—not the sudden turn of moral courage that JCI makes it out to be. Here is what the Editor in Chief has to say specifically on this matter:

Throughout 2022, the Journal has been repeatedly contacted to comment on the 2012 JCI paper. Although we cannot be certain, there now appear to be new “short and distorters.” A recent round of emails was sent simultaneously to multiple journals and editors, identifying 25 articles with potential problems and providing recommendations on how the journals should respond.

This statement is jarring. The journal saying that they believe there are new “short and distorters” implies that they believe there were already “short and distorters” contacting them in the past—assumedly, they mean the two scientists named in Cassava’s lawsuit who first found the irregularities and filed the FDA Citizen Petition. The Editor in Chief is insinuating a crime on the part of the scientists named in Cassava’s lawsuit. She does not, however, provide any evidence of a crime whatsoever. Instead, we are meant to take her word for it.

The Ethos of “Short and Distort” Accusations

As I said before and will emphasize here, “short and distort” schemes are definitely illegal and should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. This is not a novel statement to anyone who has even a cursory understanding of the stock market, but in the last couple years “short and distort” accusations have entered the zeitgeist of a troublingly large group of generally misinformed people that coalesced around the “meme stocks” of early 2021—Gamestop, AMC, Bed Bath & Beyond, etc. The general narrative is that shadowy hedge funds and market-making institutions engaged in (unsubstantiated) “naked shorting” (short selling a stock without first acquiring the necessary borrow on the underlying security) and subsequently overexposed themselves, which led them to “distort” the situation so that they could stem their growing losses. It was pretty entertaining to follow in the beginning, but it quickly turned into something that more closely resembles an apocalypse cult. Now, if you want a quick summary of “short and distort” from a crowdsourced website like Wikipedia or Investopedia you can barely make it past the first paragraph without mention of apocryphal “naked shorting.” Yes, there are real “short and distort” schemes out there; the one that JCI references is absolutely not one of them, and its promotion as such is a concoction by vocal investors with an axe to grind.

By parroting these Cassava investors and meme stock cult leaders, JCI has joined their choir. I doubt, given the ham-handed description by the JCI Editor in Chief, that she is fully aware of the discourse around “short and distort,” but all the worse if she is. It is beneath the journal to entertain it; it debases the journal’s mission to build a policy around it.

One of the biggest proponents of the Cassava “short and distort” narrative, an ultra-wealthy shareholder of the company, also repeatedly characterizes the whistleblowers that JCI alludes to as “perpetrating a genocide” on Alzheimer’s victims. Along with an insular group of other investors who coordinate routinely on Discord, he also perpetuates the conspiracy theory that Elisabeth Bik, an independent expert in image analysis, should be discredited for not disclosing all of the donors to her Patreon, and that her (again, easily verifiable) findings are tainted by this supposed conflict of interest. After failing to address concerns raised by Bik and the other scientists, conspiratorial musings about conflict of interest are now wielded by Cassava and its shareholders as a weapon to silence or discredit legitimate scientific criticism.

Corporate Influence in Scientific Publication

We witnessed something similar to this JCI editorial unfold in the The Journal of Neuroscience (JNeuro) last November, when they authorized Cassava to make statements on their behalf that grandstanded about JNeuro’s Editor in Chief clearing a paper of misconduct. In that case, after continuing inquiries by these same whistleblowers, the journal printed the “original data” that they reviewed, and it was quickly pointed out that the Editor in Chief had missed even more egregious signatures of manipulation in what was supposed to be the exonerating evidence. This led to the journal issuing an Expression of Concern, but they issued no companion statement amending the record that they authorized Cassava to establish in their stead, and Cassava’s statement sits unmodified on their corporate website to this day.

It is not typical for journals to comment publicly about their decisions to retract papers, request errata, or exonerate authors of wrongdoing, so JNeuro’s decision to remain silent about their decisions is not surprising—and yet, they apparently had no qualms authorizing Cassava to share a statement on their behalf. It’s emblematic of the dangers that corporate influence pose to scientific publishing, which is itself an incredibly lucrative industry. When whistleblowers raise flags about research that has corporate sponsors, they assume the risk of drawing that sponsor’s ire, and the consequences of assuming that risk in this particular case include a defamation lawsuit backed by the $197 million cash on hand with which Cassava can litigate to its heart’s content. Cassava states in their press release that they are “still investigating whether additional individuals or entities should be brought into this case or have separate claims brought against them,” which serves as blanket intimidation against other scientists or members of the public who might exercise their free speech rights by continuing to engage in legitimate criticism the company. This presents a far, far greater threat to scientific discourse than short selling by whistleblowers. If JCI is truly serious about disclosure, communications between the journal and Cassava Sciences and its officers, or between the corresponding author and Cassava Sciences, would be a reasonable place to start.

Pandora’s Box: Assorted Closing Thoughts

Turning back to that 2012 paper, JCI assures us that they “will always take seriously any allegations of misconduct or misrepresentation, but we will take the time needed to conduct a proper and thorough investigation.” This was not my personal experience with the journal in November 2021. When I emailed JCI to inquire about whether or not they were investigating the paper, the Executive Editor responded that their “analysis of the high resolution images provided by the author at the time of submission does not suggest that manipulation occurred. The editors have decided not to move forward with a further inquiry.” [emphasis mine] This is, in my reading, a flat refusal to take the allegations seriously, or to commit to any kind of thorough investigation.

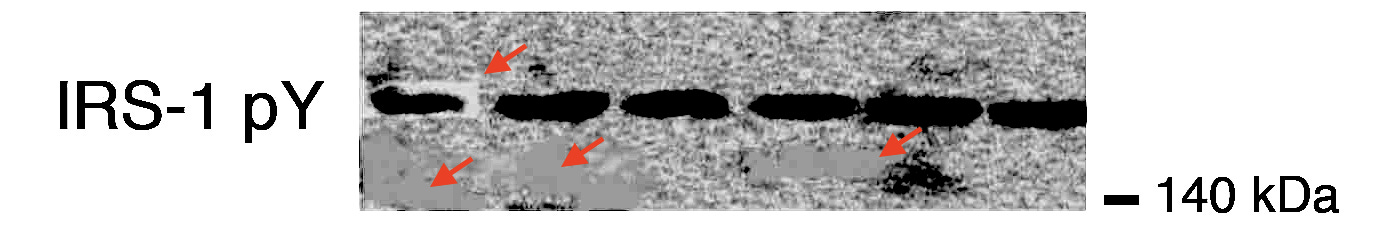

In Charles Piller’s bombshell report in Science referenced at the start of the editorial, JCI claims that the “journal analyzed high-resolution versions of the images in the first group. It could not corroborate his findings and therefore did not investigate further.” Taken in tandem with the author’s statement in PubPeer, in which he states that he “cannot provide the original scans of blots in the paper” and that JCI did not find “any problems with the published blots reexamined more recently” it would appear that at some point JCI chose to take the concerns more seriously, but in a completely opaque process without any further explanation, the journal claims it still does not see any issues. Reader, please consult a representative image from the paper below and decide for yourself:

Perhaps the only thing that the JCI editorial achieves unequivocally is the unsealing of a Pandora’s box through which it saddles itself with the role of stock market watchdog. Will the journal be taking disclosed or suspected securities positions into account when deciding what to review, or how to review it? How do they plan to “independently seek to verify whistleblowers’ potential conflicts” exactly? By requesting financial records? Will the journal be filing their misconduct reports with the SEC? How exactly do they plan to account for the “time sensitivity to short selling” if they have no reason to believe that the whistleblowing is illegitimate? By purposefully dragging their feet? Do they take on financial liability for this? Should they? Trust me, these are questions that the journal does not want to answer. That they chose to even raise them in the first place suggests that the situation may be even worse than we perceive.